As part of our Music Made Us campaign, creatives, music professionals, experts and journalists reflect on how music has been there for us through good times and tumultuous periods that inspire change. Throughout generations, music has sparked, supported and commented on movements, memories and moments in time.

Our contributors explore these events’ relationship with music – from slavery in the 1800s to the UK’s 80s acid house and rave scene and today’s Black Lives Matter movement. Here, writer Lesley Chow explores how black women ruled a decade of British music – and why they shouldn’t be forgotten.

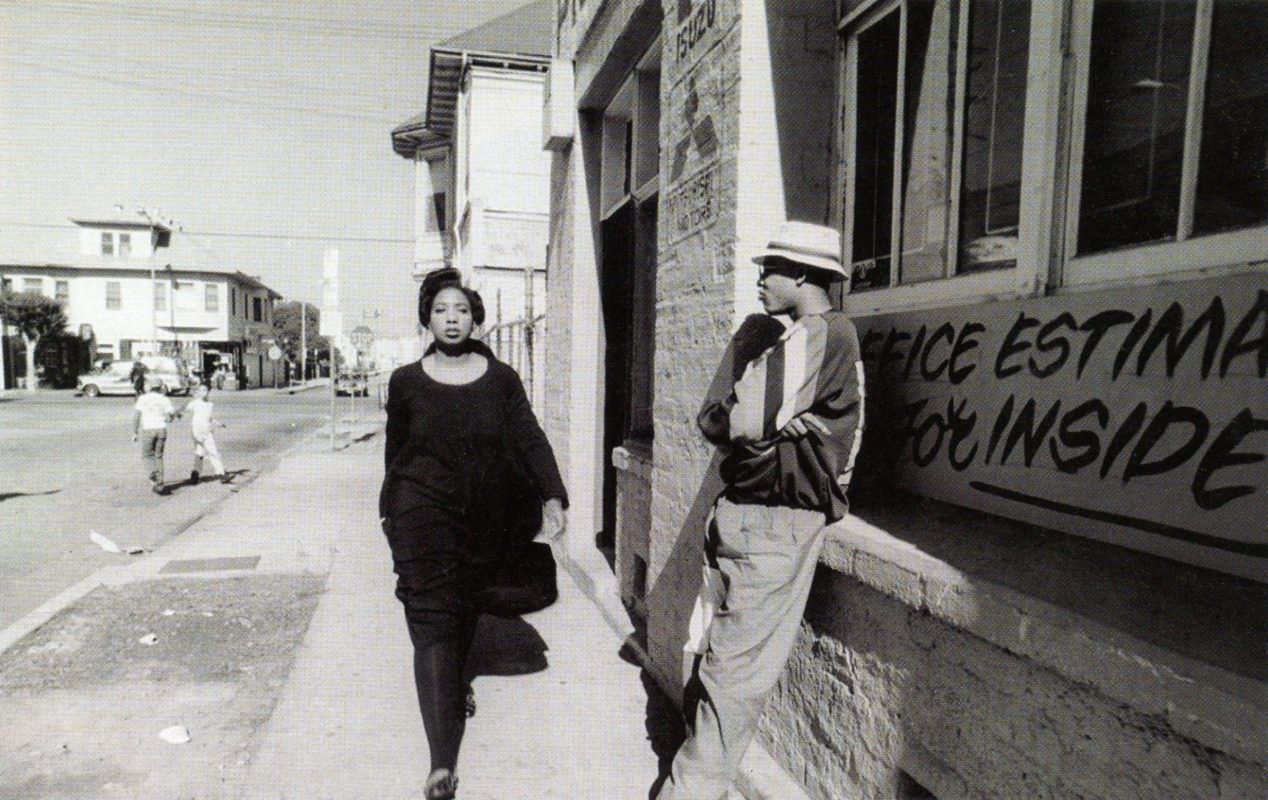

For anyone gripped by UK dance music of the 90s, there is one sound and image which dominates: Shara Nelson striding forcefully down a Los Angeles street, eyes downcast, singing “I, I, I…” in the video for Massive Attack’s “Unfinished Sympathy” (1991). Nelson’s emotional affect in that song – fierce, yet poignantly undefended – is one of the defining moods of 90s music. Thanks to Nelson’s aching voice and total immersion in character, the track is less of a torch song than a sideways glimpse into a woman’s condition. Focused on forward movement, her perspective is only partially available to us.

However, despite performing and co-writing “Unfinished Sympathy” – widely acclaimed as one of the songs of the century – and two more of Massive Attack’s greatest tracks, “Safe from Harm” (1991) and “Lately” (1991), Nelson is not a household name. How can this be? “Unfinished Sympathy” would never have existed without Nelson – it originated from a song she was writing and singing to herself in the studio – while “Lately” takes meaning from the timbre of her voice, which matches the thickest of bass sounds for depth and richness.

Earlier this year The Guardian ran a piece about black female singers whose work remains uncredited or undervalued in the industry, especially in the UK. A month earlier, an article in Zora drew attention to the number of 90s dance hits powered by black female vocalists, many of whom were sampled without permission or credit. Some took legal action, but it didn’t help in terms of name recognition or star power. Even as the records achieved huge commercial success, the women’s contributions were heard but unseen and underestimated. While Shara Nelson received credit for her work with Massive Attack, her reputation today lags behind her achievements.

Looking back at the British music scene of the 90s, I am amazed at the breadth of vocal talent. There are so many indelible moments created by black female artists, easily the high points of my pop memories. I’m thinking of Pauline Henry, the wildly gifted singer of The Chimes and co-writer of two sublime dance singles, “Heaven” (1990) and “1-2-3” (1989).

Every time she called out “Heaven!”, her voice was like an explosion of black foliage: her elated cries seem to herald a new era of soul in the UK.

Henry was part of a seemingly inexhaustible stream of brilliant black voices. The Brand New Heavies were never better than when fronted by the charismatic N’Dea Davenport, whose effortless style made their songs such an instant pleasure. Davenport is a true star in the video for “Spend Some Time” (1994), her character super-glam and shrugging off love. Tricky produced his best work collaborating with Martina Topley-Bird, her stern teenage vocals imparting cool authority to “Overcome” (1995). Another enchantress of the period is Nigerian-British Nicolette Suwoton: her voice takes on the craftiness of a genie as it undulates through Massive Attack’s “Sly” (1994). Jacqueline and Pauline Cuff, the sisters of the group Soho, took a Smiths riff and turned it into a slangy statement of defiance in “Hippychick” (1990). I’ll never forget Tasmin Archer, the auteur behind “Sleeping Satellite” (1992), which begins with a plaintive, almost chaste verse, cracking only as it reaches the climax of “man’s greatest adventure”. And there is Efua, the Ghanaian diva whose velvet voice, dirty laugh and wised-up talk in “Somewhere” (1993) made her an icon of glamour growing up, a precursor to Phoebe Waller-Bridge.

Soul II Soul worked with such an abundance of talented singers that it is easy to overlook their individual qualities – which are dazzlingly diverse in retrospect. First and foremost there is Caron Wheeler, whose calm tone controls the momentum in “Keep on Movin’” (1989) and lends itself to the eerie vacancy (“however do you want me, however do you need me”) of “Back to Life” (1989). But just as memorable are Kofi, for her seamless, gliding phrases on “Move Me No Mountain” (1992), and Victoria Wilson-James, the imperious voice of night in “A Dream’s A Dream” (1990).

More recently, there has been Bellrays singer Lisa Kekaula, teaming with Basement Jaxx for the powerhouse performance of the decade in “Good Luck” (2004). Co-written by Kekaula, the song is a late-breaking soul classic which remains underrated: her work here ranks with the best of Aretha, delivering the reality check of “You’re so totally deluded” and working up a head of steam as she recalls “how you sold me down the river”.

Thinking back, I begin to wonder if my memories of British pop aren’t almost entirely shaped by black female singers.

These women were my supreme standard of what a voice, an energy, a distinctive presence, could bring to music. Each one had a unique timbre and defining aesthetic, potentially the stuff of Adele-like cults and global careers. As a child, I fully expected that Kofi, Nelson, Wheeler, Suwoton and Topley-Bird would become stand-alone stars in the next decade – I assumed that these women were only the start of a wave.

It never happened. It turns out that there was a cap on the number and type of female stars the marketers would allow, and none of these women seemed to fit the bill. Although some went on to release solo albums, they never got the push or acknowledgement they deserved, from an industry that perceived them as session singers rather than creative, individual artists.

It was an egregious waste of talent. It seems absurd that a voice and presence like Pauline Henry’s could fail to become ubiquitous, and certainly not for lack of glamour or pizzazz. To reach the next level internationally, she needed the promotion and the producers – in other words, the pop machine – to get behind her and believe in her. As for Tasmin Archer, the author of “Sleeping Satellite” should have been a shooting star, instead of becoming known as a one-hit wonder in the US. But from the late 90s onwards, record companies were more focused on crystallising the look of the moment, from Sophie Ellis-Bextor to Rita Ora, than finding singular voices.

Today, even a remarkable performer such as Estelle commands a fraction of the press of a Dua Lipa or Jess Glynne, and as the Guardian article notes, it wasn’t until she “went Stateside that she blew up.” The sound of Estelle reminds us of what a great singer should be: a voice that has us reaching not only for superlatives but for ways to describe its curious effect, its idiosyncrasies of tone. She has a timbre that’s absolutely one of a kind: husky yet streamlined, mellow and warm but with a cool sheen on top (a correlative to the silvery lipstick she often wears). Her artistry isn’t just about a great set of pipes or hitting impossible notes, but a feel that’s distinctively hers. It’s a quality that all the greatest living voices have, from Anita Baker to Randy Crawford to Chaka Khan – and Pauline Henry.

Listening to Estelle reminds me of the wealth of black British talent we were lucky enough to experience in the early 90s, and how limited notions of celebrity kept them from progressing even further. Nelson, Wheeler and Henry still define my ideas of musical perfection: I don’t think their examples have ever been equalled.

Lesley Chow’s book, You’re History: The 12 Strangest Women in Music, will be released by Repeater in March 2020. You can pre-order your copy here.

Listen to all the artists featured in the article here:

Our Music Made Us campaign is told through the students, graduates, journalists, experts and passionate people who have been shaped by music. Discover their stories here.