As part of our Music Made Us campaign, creatives, music professionals, experts and journalists reflect on how music has been there for us through good times and tumultuous periods that inspire change. Throughout generations, music has sparked, supported and commented on movements, memories and moments in time.

Our contributors explore these events’ relationship with music – from slavery in the 1800s to the 1992 LA riots and today’s Black Lives Matter movement. Here, James Kendall, Course Leader, BA (Hons) Music Marketing, Media & Communication, explores how political decisions and a changing society gave birth to acid house and rave in the UK.

If you only know one thing about British acid house’s origin story, it’s probably this: four DJs went on holiday to Ibiza and came back with the blueprint for the modern clubbing scene. It was Paul Oakenfold’s 24th birthday, and to celebrate he took Danny Rampling, Nicky Holloway and Johnny Walker to Amnesia, where Alfredo was playing a blend of music that these four DJs and club promoters had never heard before.

“All four of us changed that night,” said Danny Rampling. “I can remember saying, ‘I think we may be on to something here.’”

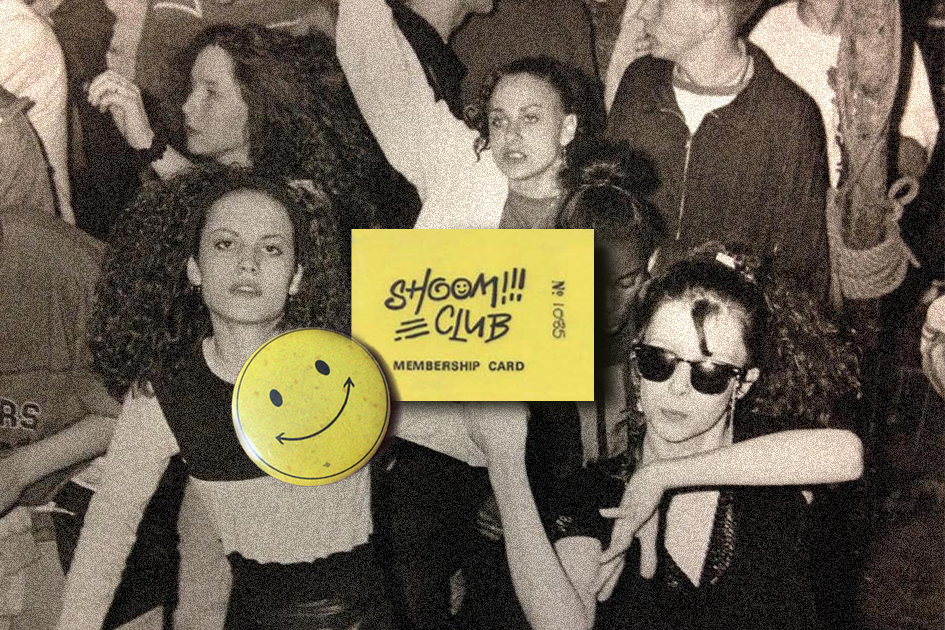

Undoubtedly, he was right. A year later, known as The Second Summer Of Love, Oakenfold had started Spectrum, Rampling was running Shoom, and Holloway’s The Trip was in full flow, and club culture was changed forever. Twelve months after that and the M25 was full of tens of thousands of clubbers every weekend heading to outdoor raves, the police doing everything they could to stop them. By the end of the 90s, every town had a club playing dance music, and superstar DJs were demanding thousands of pounds per set. Last year, Marshmello earned $40m. Yeah, the guy with the bucket on his head. Admittedly, that probably wasn’t where the peace-love-and-unity Ibiza idealists saw this going.

All art is a product of its environment, and this was the environment that acid house and rave were being born into. Young people had very few options open to them as the Tory party dramatically stripped back support and services, especially across inner cities and the north of Britain. But Thatcherism also promoted entrepreneurism – get on your bike, look after yourself, make your own opportunities – and that’s what the people who changed club culture embraced, putting on parties, starting record labels and fashion brands. However, they didn’t always worry too much about which side of the law they were on.

“The youth were reclaiming spaces that had been left behind, just as acid house and rave were claiming young people that had been left behind.”

Start the Dance

Throwing parties in warehouses or in fields wasn’t illegal, yet, but permission wasn’t always asked for when you had a good set of bolt cutters and a powerful generator. Many lessons were learned from the soul and rare groove warehouse scene that had grown up when working-class and, especially, black clubbers had been denied access to city clubs. There was no shoes-and-shirts rule here. The youth were reclaiming spaces that had been left behind, just as acid house and rave were claiming young people that had been left behind.

“The DJ might get their name on the flyer, but it was the crowd on the dancefloor that was the real star of the show – a group in unity, through the beat.”

The legality issues didn’t stop with the settings of the parties. It would be disingenuous to ignore the fact that acid house and the rave scene was fuelled, to a degree, by drugs. With its breaking down of barriers and inhibitions, Ecstasy made sense to a group of people denied a community. The myth is that rival football hooligans put down their broken bottles to hug on the dancefloor. Though this was perhaps not a common occurrence, certainly bonds were created across race, class and geography. The DJ might get their name on the flyer, but it was the crowd on the dancefloor that was the real star of the show – a group in unity, through the beat.

Those clashes with the miners’ strike (and similar battles with new-age travellers) that these teens and 20-somethings had been seeing on the news every night – combined with a feeling of being left outside of politics and opportunity – had undoubtedly created a feeling of ‘them and us’. With the communities that the positive messages in the music and the stimulants had driven, the feeling of ‘us’ was strong. And so, unfortunately, was the ‘them’.

It couldn’t last forever though, and the Tory MPs whose constituents were kept awake by the music started to be more vocal about the raves. Already The Sun and ITV had fanned the flames of a moral panic around acid house, and by 1990 tensions were getting strained. The potential to earn huge amounts of money dealing drugs or running security had caught the attention of established gangs, who were competing for the business in a way that was very much at odds with the people and love vibe of the ravers.

Tory MP Graham Bright introduced a bill that would be very specific in the parties it was aiming to outlaw – those with ‘repetitive beats’. Dancing outdoors was about to become illegal. Dance music historian Bill Brewster believes that the breweries were also leaning on politicians to get people back into clubs and pubs on a Saturday night. Castlemorton – a free festival, initially for travellers, that would attract 40,000 ravers to outskirts of a sleepy village for a week-long party – would be the scene’s swansong. The right to gather would be rescinded.

Ultimately, the politicians and tabloid press won, and dancing – festivals aside – would return to clubs. But things had changed. For a start, dance music remained. So, what of the music? It’s important to note that house music didn’t just appear fully formed in Shoom on December 5th, 1987. From the ashes of disco, two black gay clubs in Chicago – Ron Hardy’s dark Music Box and Frankie Knuckles’ The Warehouse (and later The Power Plant) – emerged to keep that sound alive and bring it up to date for the 80s. “House ain’t nothing but a harder kick drum than disco,” said Farley Jackmaster Funk, a true Chicago house pioneer. “That’s it.”

From there it spent three years permeating through Manchester and the north of England, not least in the Hacienda. Black dancers in Manchester community centres were embracing house music as early as 1986, while it hit selected gay clubs in London through 1987. Farley Jackmaster Funk’s ‘Love Can’t Turn Around’ reached the top ten in ‘86, while Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley took ‘Jack Your Body’ to number one almost a year before Shoom appeared. Hacienda DJ Mike Pickering was not just playing house music before the Ibiza trip DJs, he was making it with his band T-Coy.

“Being first out of the gate of the post-Ibiza clubs, Shoom gave the culture an identity.”

So, if Paul Oakenfold and his mates didn’t invent dancing all night, mixing or even play house music first, what was the importance of that Ibizan trip? Why the legend? Being first out of the gate of the post-Ibiza clubs, Shoom gave the culture an identity – with the smiley face logo, baggy clothes, arms aloft dancefloor moves and you’re-my-new-best-mate hugs.

“Before then it didn’t have a look, a dance,” says DJ and producer Terry Farley.

“So perhaps we should thank the government for acid house and rave. They might have kept us indoors, but they never stopped us dancing.”

“The culture of dance music – you can say its beginnings were at Shoom,” adds club owner and DJ Mr C.

Shoom (and the other nights that came from that legendary Ibiza trip) was the spark, but the fuel was the pent-up energy of a generation that was desperate for community, opportunity and a sense of purpose. So perhaps we should thank the government for acid house and rave. They might have kept us indoors, but they never stopped us dancing.

WANT TO FIND OUT MORE?

Here’s a reading list of books that help tell the story.

- Altered State: The Story of Ecstasy Culture and Acid House (Matthew Collin)

- Last Night A DJ Saved My Life: The History Of The Disc Jockey (Bill Brewster)

- Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music And Dance Culture (Simon Reynolds)

- The Record Players: DJ Revolutionaries (Bill Brewster & Frank Broughton)

- Superstar DJs Here We Go!: The Rise and Fall of the Superstar DJ (Dom Phillips)

- The Haçienda: How Not To Run A Club (Peter Hook)

- Rave On: Global Adventures In Electronic Dance Music (Matthew Collin)

- Sonic Youth Slept On My Floor: Music, Manchester, And More: A Memoir (Dave Haslam)

Our Music Made Us campaign is told through the students, graduates, journalists, experts and passionate people who have been shaped by music. Discover their stories here.