As part of our Music Made Us campaign, creatives, music professionals, experts and journalists reflect on how music has been there for us through good times and tumultuous periods that inspire change. Throughout generations, music has sparked, supported and commented on movements, memories and moments in time.

Our contributors explore these events’ relationship with music – from slavery in the 1800s to the UK’s 80s acid house and rave scene and today’s Black Lives Matter movement. Here, Joel McIver, Author and Music Journalism Module Leader, examines how a world-dominating stream of Hip Hop emerged from a certain cataclysm. It’s 28 years since one of the greatest moments of civil disobedience in American history – the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

On April 29, 1992, thousands of American citizens switched on their television sets to witness the sight of burning buildings, looted stores and crowds of people in conflict with gangs of heavily armed, but outnumbered, law enforcement officials. Was this yet another report from the Gulf War, then at the top of the news headlines? No – these scenes were being transmitted from closer to home: Los Angeles.

To an extent, the 1992 LA riots were expected. A case had been simmering along for the previous 14 months, focusing on the alleged brutality of four police officers to a motorist in northern LA. The motorist’s name was Rodney King, and the four police officers were Sergeant Stacey Koon, Officer Larry Powell, Officer Theodore Briseno, and Officer Timothy Wind. A jury in Simi Valley, in California’s Ventura County, had come to the verdict that all four cops were not guilty, despite film footage of the King incident, in which he had been visibly assaulted.

It seemed that many of the residents of Los Angeles agreed. As the nation watched, transfixed, reports of the biggest civil disturbance in the country’s history began flooding in. Six days of destruction followed, leading to the deaths of 63 people, 2,383 injured citizens, over 12,000 arrests, and property damage in excess of $1 billion, which is almost double that figure by today’s standards.

Multiple contributory factors to the riots were later acknowledged, although not necessarily from America’s leaders. The Republican government, led by President George H. W. Bush and his Vice-President Dan Quayle, were broadly unsympathetic to the stifling living conditions and racial tensions prevalent in some parts of LA. Asked only a month later about what might have provoked the violence, Quayle refused any deep analysis, shrugging: “My answer has been direct and simple. Who is to blame for the riots? The rioters are to blame. Who is to blame for the killings? The killers are to blame.”

This was the background for the decision of thousands of Los Angelenos to turn on their own city. Almost three decades later, it seems to many who remember the 1992 disturbances that it was primarily the beating of Rodney King which caused them – but in retrospect, his involvement was merely the last in a long line of incidents, each of which raised the temperature of inner-city LA. Most prominently, this occurred in poorer areas such as South Central, where the anger felt by many of the city’s oppressed residents eventually reached breaking point.

More serious indications of the state of the nation – which by ’92 had endured a decade of Republican policies – could be seen in the decay of the city ghettos, a direct result of the deprioritisation of the urban poor by the federal government under Ronald Reagan and now Bush. Although the global recession that had plagued economic growth in those years had affected everyone, not just residents of run-down city districts, its impact on suburbs such as Compton had led to a measurable increase in crime and a quantifiable rise in poverty. Couple this with the often over-zealous reaction of the police to the increased urban crime levels in these areas, and all the explosive atmosphere required was a spark to ignite it. In this case, the spark was Rodney King – but the broader picture is that years of reduced domestic spending had prepared the ground for the rioters.

The phrase ‘cop killing’ was in the news at the time.

The Rise

To add to the tensions, the phrase ‘cop killing’ was in the news at the time. On March 30 1992, the rapper Ice-T released the self-titled debut album by his heavy metal side project, Body Count, on the Warner Brothers label. Metal fans were only mildly interested, as it was neither as heavy nor as exciting as Ice had fondly imagined, and hip-hop fans were slightly bemused: the album didn’t make many waves with either audience and slipped out of the chart.

However, the album’s song ‘Cop Killer’ rapidly gained attention, causing two police organisations, the Dallas Police Association and the Combined Law Enforcement Association of Texas, to campaign Warners to remove the song from the Body Count album. After the protest gained support from police associations in California and New York, Alabama governor Guy Hunt asked state record stores not to stock the product, Dan Quayle labelled the song “obscene”, 60 members of Congress signed a letter addressed to Warners which described the song as “despicable” and “vile” – and the California State Attorney General asked his state’s retail outlets not to sell the album.

The final straw came when President Bush spoke out, denouncing any record company that would release a product of this nature, and then Warners’ shareholder Charlton Heston made a bizarre appearance at a meeting on July 15 where he read out the lyrics of two Body Count songs. Two weeks later, Ice-T publicly announced that the song would be removed from all future copies of the album. “In a war,” he later explained, “and make no mistake, this is a war, sometimes it’s necessary to retreat and return with superior firepower.” Seven months later, Ice-T and Body Count terminated their contract with Warners.

All this was reflected in hip-hop music throughout the Nineties. Consult the Washington Times journalist Lou Cannon’s book, Official Negligence: How Rodney King And The Riots Changed Los Angeles And The LAPD, for evidence. In the book, Cannon revealed relevant observations from hip-hop artists such as Ice Cube and Ice-T. As those commentators saw it, the LA police department was riddled with institutional dysfunction, embracing racial bias wholeheartedly and applying those principles to the execution of their work. Film director John Singleton was telling the truth, it seems, when the cops arrived hours too late to be of any use after the burglary in his 1991 film Boyz N The Hood – and when Public Enemy said that ‘911 Is A Joke’ in 1990, they knew what they were talking about.

“Just read the right books and listen to the right music, and it all makes sense.”

On his album Amerikkka’s Most Wanted, released two years before the riots, Ice Cube had proven to be a prophet, and a deadly accurate one at that. One rhyme ran, “Every cop killing goes ignored… To serve, protect, and break a n-’s neck”? Ice-T had also painted the picture of an LAPD made malignant by racism a dozen times – and of course, Cube’s old band NWA hadn’t written ‘Fuck Tha Police’ in 1988 out of boredom. The primary, albeit not the sole, cause of the LA riots was the racism of the police – just read the right books and listen to the right music, and it all makes sense.

‘Gangsta’ soon became a widely known and used adjective in music circles, having penetrated mainstream awareness, and took another step upward with the arrival of G-Funk, a play on words based on the Seventies band P-Funk, or Parliament-Funkadelic. This was primarily the innovation of Ice Cube’s sometime NWA bandmate Dr Dre, whose first solo album, The Chronic, appeared on December 15 1992.

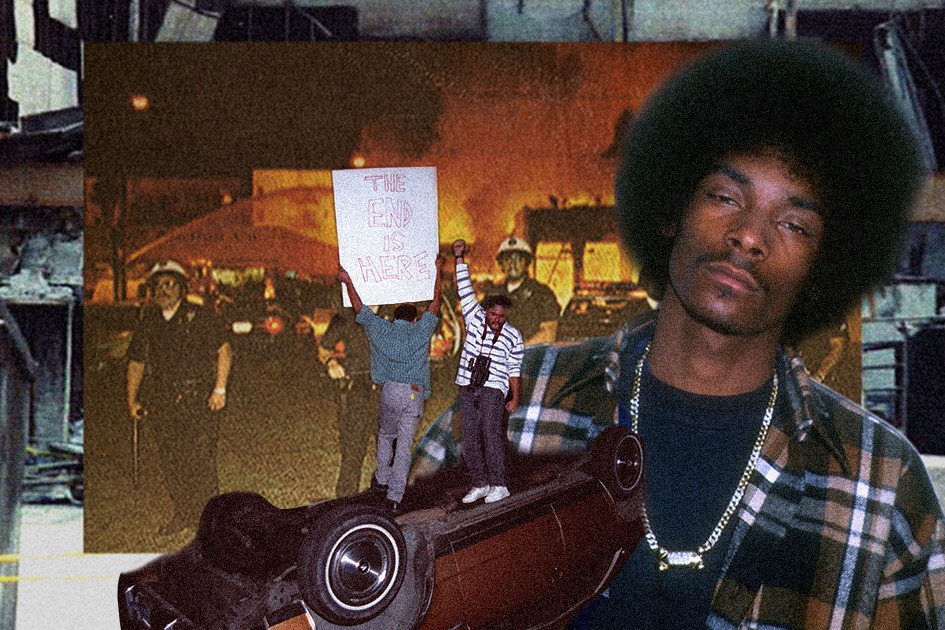

The album’s impact was long-lasting and launched the career of a young rapper named Calvin ‘Snoop Dogg’ Broadus, among others. Snoop later said of The Chronic: “Death Row put the West Coast on the map – The Chronic was the album that did it. We put gangsta rap on a worldwide scale. Without the business, the music wouldn’t be respected.”

The face of hip-hop was changing elsewhere, too.

The face of hip-hop was changing elsewhere, too. As the West Coast movement grew, helped along by Cube, Dre, Snoop and later Tupac Shakur, the East Coast-based scene, where hip-hop had been born in the mid to late 1970s, began to seize commercial ground. Prominent among these was a unique collective from Long Island called the Wu-Tang Clan, a group of nine rappers and producers who based their philosophies on the teachings of the Shaolin Temple. Their first single, “Protect Ya Neck”, had made an underground impact before its official release attracted attention away from South Central and back to the equally intimidating streets of New York.

Around this time, the first use of the term ‘East-West rivalry’ was noted, with the idea being that the two equally powerful hip-hop communities were beginning to take offence at the other’s success. Insults were exchanged and the more intelligent members of the rap scene prophesied violence. One rapper who voiced his unease was Cypress Hill’s B-Real, who warned that internal strife within the hip-hop world was a wrong move.

“Artists such as Dre and Snoop had attained a platform for expression which had never been dreamed of.”

As 1992 came to a close, gangsta rap had risen, fallen and been supplanted by G-Funk, directors such as John Singleton had won the film world’s most prestigious awards and the nation had been in outcry over ‘Cop Killer’. Artists such as Dre and Snoop had attained a platform for expression which had never been dreamed of. This was all reflected in music, based around the issue of racial tensions.

Whether we are closer to widespread racial harmony in 2020 is a matter of perspective: no matter what the answer may be, the musical commentary on the issue which emerged after 1992 has profoundly informed the debate – and will continue to do so.

Want to find out more?

Here’s a reading list of books that help tell the story.

- The Rose That Grew From Concrete (Tupac Shakur)

- The Wu-Tang Manual (RZA And Chris Norris)

- Black Privilege: Opportunity Comes To Those Who Create It (Charlamagne The God)

- God Save The Queens: The Essential History Of Women In Hip-Hop (Kathy Iandoli)

- 3 Kings: Diddy, Dr. Dre, Jay-Z, And Hip-Hop’s Multibillion-Dollar Rise (Zack O’Malley Greenburg)

- Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History Of The Hip-Hop Generation (Jeff Chang)

- 6 N The Morning: West Coast Hip-Hop Music 1987-1992 & The Transformation Of Mainstream Culture (Daudi Abe)

- Fight The Power (Chuck D)

- Hip Hop America (Nelson George)

Our Music Made Us campaign is told through the students, graduates, journalists, experts and passionate people who have been shaped by this creative outlet. Discover their stories here.