As part of our Music Made Us campaign, creatives, music professionals, experts and journalists reflect on how music has been there for us through good times and tumultuous periods that inspire change. Throughout generations, music has sparked, supported and commented on movements, memories and moments in time.

Early March 2020 was like any other year in the music calendar. Festivals were finalising their lineups, artists were gearing up for the touring season, and fans were snapping up tickets in preparation for the summer.

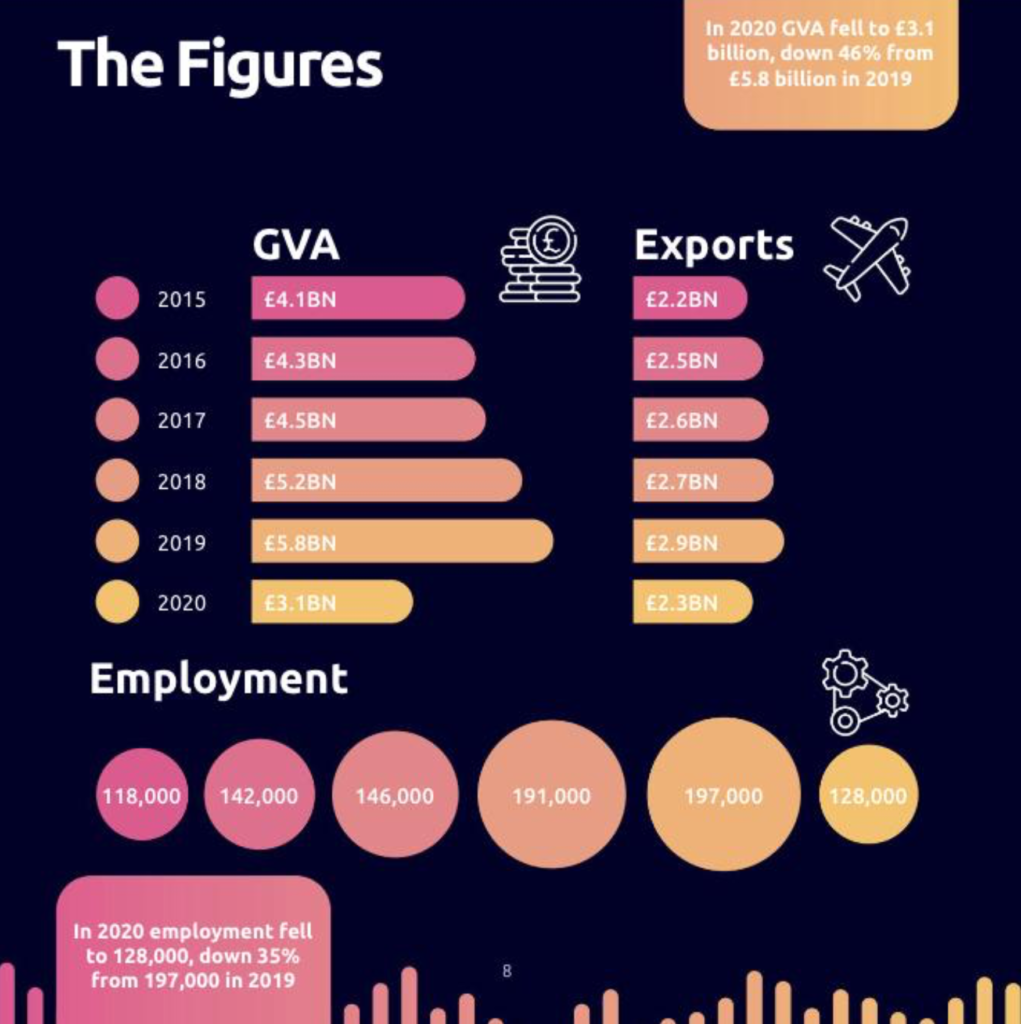

The UK music industry was on course for another successful 12 months, as employment rates were approaching a high of 200,000 workers nationally, and the Gross Value Added (GVA) was expected to grow on its £5.88 billion turnover, having increased steadily in the five years prior.

When the Coronavirus pandemic began as a far-flung story some 5,500 miles away from the UK, nobody quite expected it to change people’s daily lives and the global economic landscape for years to come.

For this article, I spoke to artists and industry professionals to explore the effects of the pandemic, the challenges of isolation and unemployment, and how this is now shaping the post-pandemic music industry of today.

Source: UK Music 2021 Music Economy Report

Following the first 12 months of the pandemic, UK Music reported a £2 Billion fall in GVA and a 35% drop in employment figures.

As an industry that thrives on human connection, it suffered a severe blow due to the cancellation of events and the closure of venues, studios and offices. Some of which were to close permanently.

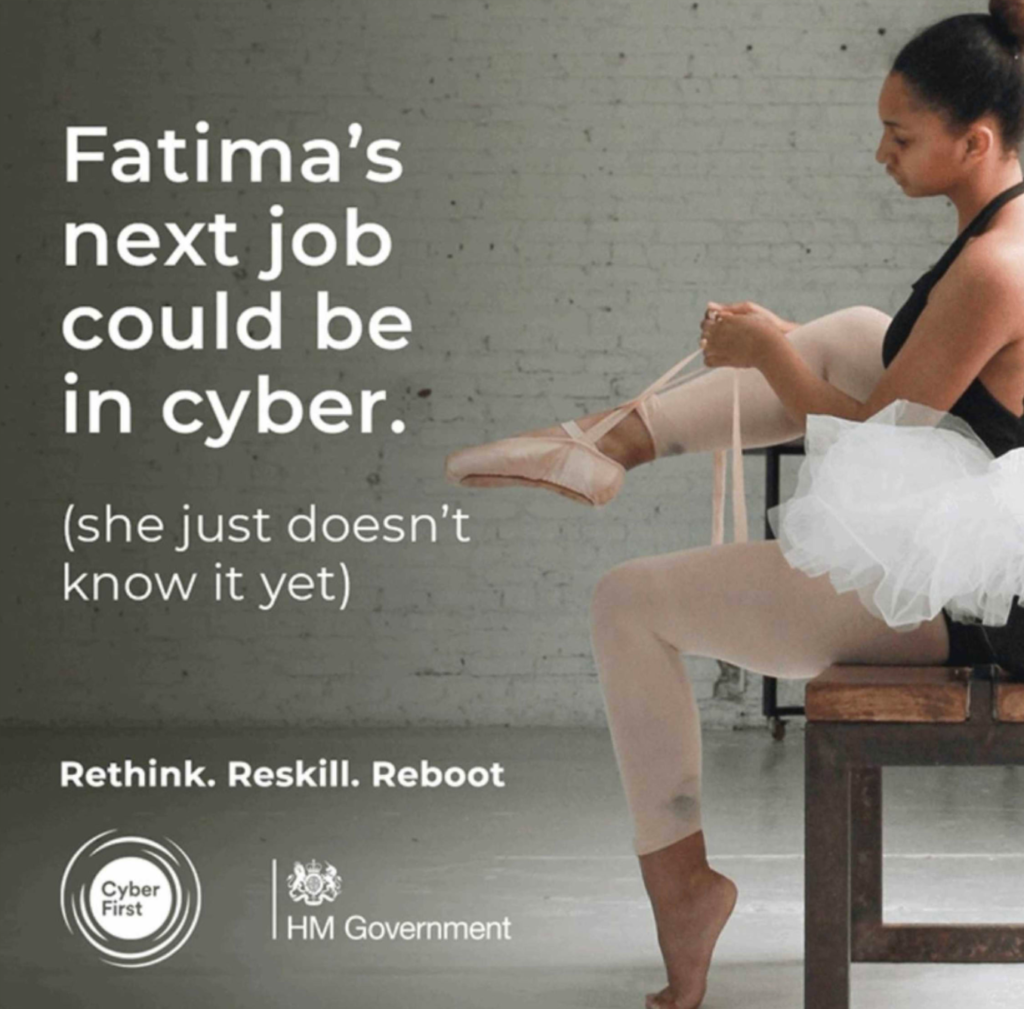

The bleakness in the figures was accompanied by governmental pressures, such as the heavily lambasted ‘Rethink. Reskill. Reboot.’ campaign; its underlying message encouraging workers in the arts to give it up and find work elsewhere.

Further comments from Chancellor Rishi Sunak supporting the idea caused an even wider gulf between artist communities and the government. Tim Burgess (The Charlatans) wrote his opinion in The Guardian:

“I’m guessing Sunak wasn’t suggesting Ed Sheeran should become a plumber’s mate. But what happens when the Ed Sheerans’ or Adeles’ of the future abandon their dreams, and we’re left without artists bringing in those billions and inspiring others in the future?”

It was a popular opinion mirrored by many others.

But despite the romanticism, some felt the harsh reality first-hand when there was no longer the need or the funds for the predominantly self-employed roles, which were not entitled to the support schemes in place.

Work within the arts was dismissed as a pursuit of passion over finance and luxury that a vast majority would not be able to afford. As a result, many did heed the advice to move into different lines of work. This included the artists themselves, all at different stages of their careers. Every element was affected – from creating, promoting and touring to releasing music.

We are now beginning to see the product of these effects.

The effects of the pandemic on artists’ creativity and promotional activities

London-based rapper Bushrod felt the impact of lockdown on his creativity:

After losing his side job in graphic design due to the pandemic, he leapt to pursue music full time, which he recognised as a bold move requiring adaptive DIY methods:

“It was difficult, but it was now or never; gigs weren’t happening and everything was up in the air. But it was a good chance for many artists to work on different ways to promote themselves and work on music independently. So it was a blessing in disguise, kind of.”

“Before Covid, I was keen on signing to a label, and I’m not sure what it was about Covid that changed that idea. But I suppose it just put things into perspective.”

Independent artist Abi Rose Kelly was at the beginning of her career in 2020 and had just released her debut single, James’ Corsa.

“My motivation was gone, and I didn’t pick up a guitar for a long time. I didn’t realise it at the time, but when I got back to gigging, it was a little spark that left your life for so long. Networking at gigs is so important for getting a start in the local scene. It felt like I was releasing music to no one at times because there was none of that connection.”

Interestingly, both Bushrod and Abi Rose Kelly went through a similar shift in priorities over lockdown. They became less motivated to land a record deal and instead to become more independent as artists.

“Later on, when we came out of lockdown, I felt like I’d adapted to writing music for myself again instead of trying to become this next big artist. It made me remember why I started making music in the first place.”

This posed the question of whether record labels have noticed a shift in artists’ needs for a label over lockdown or whether independence is becoming more of an accepted factor in artists’ careers.

Manchester label Sour Grapes Records specialise in cassette releases and have always allowed artists to work on their DIY processes alongside their agreements with the label.

The Sour Grapes Team co-owner, Giorgio, agrees that while artists have shifted their mindsets to more DIY methods, this was prevalent well before the pandemic, and this independence is something that Sour Grapes actively support.

“We are very open-minded, and this is exciting for bands. The music is yours; we just sell the tapes! Some of the bands that work with us had more time to write new music and get tighter, which was one positive of the pandemic. We live in a world where you have to work all the time, and you wish you had time to sit down and think about what you wanted to do.”

The temporary extinction of the live sector

The most significant sector to take a hit was, of course, live music. Joe Cockburn, Head of Live at Manchester and label, Scruff of The Neck, had moved into the sector in September 2019 and was preparing for his first summer touring season before all plans were scuppered.

The enforced cancellations and rearranged dates have resulted in a backlog of shows extending for months and, in some cases, years behind for promoters:

“We’ve got a show, Giant Rooks, in July, which is on its fifth rearranged date. People don’t want to part with their money until they know the show is definitely going to happen. Another tricky thing with rearranged dates is that a lot of people forget that they have a ticket, which results in quite a large drop-off.”

Now that live events have returned, Joe believes that artists will utilise its regeneration by touring as much as possible and that we’ll start to see more overseas artists performing in the UK:

“It’s not just the ticket money that the bands are missing out on, but the merchandise too, which is probably the most lucrative source of income for an artist.”

As well as artists, crew and promoters, the UK’s music venues received the brunt of the pandemic. With no way to generate income, owners were still required to pay rent for their premises, which affected the majority of the UK’s beloved venues.

Renowned Manchester venues, Gorilla and The Deaf Institute gained national attention when they came close to shutting down before being bought out at the last minute. This was one of the positive outcomes amidst countless other struggles venue owners and their teams felt.

The Music Venue Trust played an instrumental role in trying to help the nation’s independent venues during the most challenging times. Donating or buying merchandise from their website is possible to support the work and the venues involved.

The cut-off of a vital source of income through live shows meant that digital media was more prevalent than ever. While online advancements such as streaming and social marketing have spearheaded the industry since well before the pandemic, it gained a considerable boost when it became the only accessible medium for work and connecting with a broader audience.

This resulted in many artists and businesses shifting their strategies online to sustain their careers.

One front-running strategy was via the social platform TikTok, making artists more reachable than ever to its growing 1.1 billion users through short snippets of content.

Indie outfit The Wombats utilised the platform to achieve some of the highest listening figures in their 20-year career. I previously discussed it with bassist Tord Overland Knudsen for Northern Exposure Magazine:

“I haven’t even got the app, but people in media were like ‘you need to be on TikTok!’

We wondered why ‘Kill The Director’ suddenly started streaming way more than any other song. One or two lines from the verse went viral and that’s how we found out about it. We were like, ‘what the f*ck?’ Like hundreds of thousands of people recreated it, and then it affected the streams.”

Stuart Daley, co-owner of promotion and management company The Pentatonic, shifted all focus to supporting rostered artists digitally during the lockdown:

“It was about ensuring the bands had content ready to go out and everyone was still active online.”

It wasn’t just the use of short-form content that was furthered in the pandemic, but also full-length, live-streamed shows which were the next best thing to performing in front of an audience.

Its widespread introduction allowed artists to showcase their live work still, although Stuart noticed the playing field became very saturated, very fast:

“Everyone loved it for a while, but then I think there was too much towards the end. It got to a point where there were some quite high-budget videos – I think it was Tom Grennan’s live stream where you could virtually walk around the venue, and it had got to a point where people were asking, ‘Is this the way it’s going to go? Is it going to be all online from now?’ Now live shows are back, I think things should go back to a relative norm.”

What does this mean for the future of the music industry?

As the first ‘normal summer’ since 2019 approaches, 2022 will hopefully be a cause for celebration as the industry is now well into its regeneration process.

This veiled optimism is justified though, as the figures look much more positive. BPI recently reported a 12.8% revenue jump for the UK music industry between 2020 and 2021, which will expand as more figures are released to mark the end of the financial year.

A jump in revenue means an influx in job opportunities, which will pave the way for reaccessing the industry. The digital marketing sector is stronger than ever, and the live industry is crying out for more workers as shows and festivals are rebooting to full schedules.

2020 was a time in history that is still being unravelled, and the long-term effects might not be evident for years. There is still much to be explored, such as the depth of the industry and its sectors and the pandemic’s effects on health and personal well-being. (More information and support on this is available through Musicians Union.)

Even before the pandemic, the music industry was renowned for its challenges, and navigating the potholes is something that its artists and workers are well accustomed to. The saying that ‘adversity breeds innovation’ is a relevant summary of the current landscape. This can be applied not only to the music industry off the back of the pandemic but also globally.

Thank you to the interviewees for contributing their knowledge and insight:

Abi Rose Kelly – Artist

Lockdown song: Jamie Webster – Knock At My Door

Bushrod – Artist

Lockdown song: Loose Puppet – Living In A World Postponed

Giorgio – Sour Grapes Records

Lockdown song: PowerSolo – Step Back (Available via Sour Grapes Records)

Joe Cockburn – Head of Live at Scruff of The Neck

Lockdown song: Everything Everything – Supernormal

Stuart Daley – Owner of The Pentatonic

Lockdown song: Uno Mas – Jungle

Reading Recommendations:

The Lockdown Interviews: Interviews With Some of Music’s Biggest Stars – Richard Blade

Performance In A Pandemic – Laura Bissell, Lucy Weir Music: The Business (8th Edition) – Ann Harrison

Good Pop Bad Pop: Not A Life Story, But A Loft Story – Jarvis Cocker (released May 26th)

The Post-Pandemic Business Playbook – Ofer Mintz