As part of our Music Made Us campaign, creatives, music professionals, experts and journalists reflect on how music has been there for us through good times and tumultuous periods that inspire change. Throughout generations, music has sparked, supported and commented on movements, memories and moments in time.

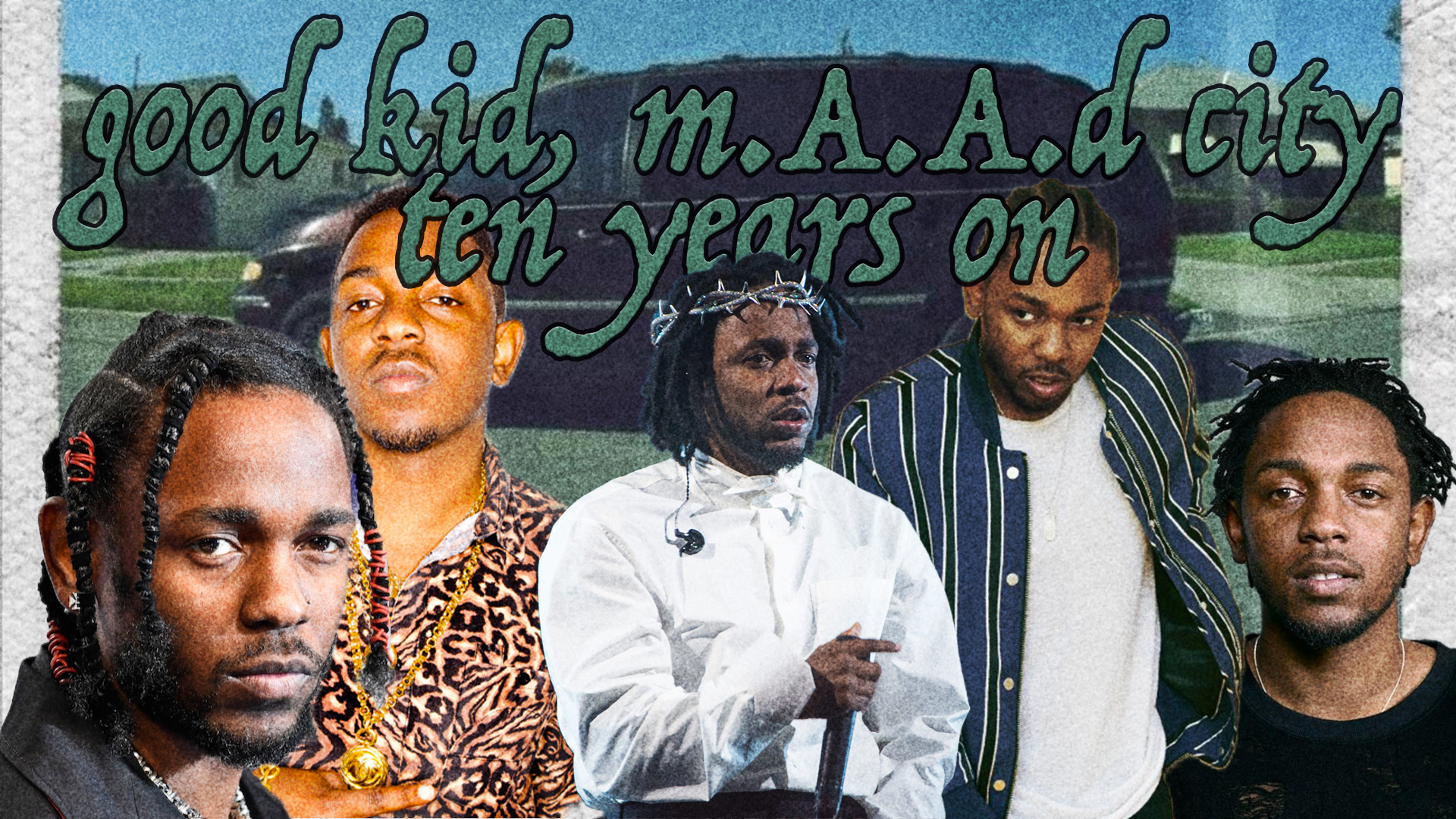

Our contributors explore these events’ relationship with music – from slavery in the 1800s to the UK’s 80s acid house and rave scene and today’s Black Lives Matter movement. Here, Marketing, Media and Communications student James Mellen explores the impact of Kendrick Lamar’s sophomore album, good kid, m.A.A.d city.

‘My Angry Adolescence Divided’ and ‘My Angels on Angel Dust’ poetically sum up what can now be considered a classic album, not just one of the best records of the 2010s. Compton native Kendrick Lamar’s sophomore record—and let’s face it, the first one is hardest to get right—proved he had more to offer than the majority of his up-and-coming contemporaries, including artists like J. Cole, ScHoolboy Q and Meek Mill. The album’s release in October 2012 was met with rave reviews, Grammy nominations and universal critical reception, with whispers of the intimidating term ‘instant classic’ – but a new album cannot, by definition, be a classic. Ten years later, however, Kendrick Lamar’s has stood the test of time and cemented itself in history as a hip-hop classic.

Ranking Lamar’s discography is incredibly controversial within the hip-hop community (some of the Reddit threads about good kid, m.A.A.d city vs To Pimp a Butterfly will have you in the hip-hop-head rabbit hole for hours). Today is not about making a case for good kid being better than any of Lamar’s other releases but more about discussing the impact, relevance and how such a layered and intricate record still holds up ten years on. Or, rather, how a ‘short film by Kendrick Lamar’ presents itself almost a decade later.

The non-linear narrative of good kid, m.A.A.d city, has Kendrick Lamar chronicling his experiences in Compton, his hometown, and its brutal, harsh realities. He details the hedonistic desires of Compton natives and West Coast rappers, along with consistent themes of gang violence and economic disenfranchisement, among many others. Lamar weaves through various characters and stories, atop atmospheric, downbeat production, much of it reminiscent of older rap sounds. The dusty, vinyl-crackled beats across the album are redolent of eighties and nineties West Coast and gangster rap production. The title of the record itself is also thought to be a reference to WC and the Maad Circle, a West Coast hip-hop group who were prevalent from the early to mid-nineties when Lamar was a child and beginning to discover and fall in love with rap music.

Most commonly, good kid, m.A.A.d city is compared to albums by OutKast – mainly their 1998 record Aquemini and flecks of 1996 record ATLiens. Though not presented chronologically, good kid, m.A.A.d city shows Lamar’s development from an impressionable, romance-seeking teenager to a centred, self-aware adult, as well as honing in on the horrific scenes he witnessed along the way. While the narrative of the album is arguably not as complex as To Pimp a Butterfly, it serves a different purpose. good kid, m.A.A.d city is a personal record, one that is steeped in idiosyncratic memories and experiences. By contrast, To Pimp a Butterfly is a celebration of black music, with the lyricism being steeped in politics and history. The main focuses lyrically are African American culture, discrimination, racial inequality and injustice, as well as mental health issues like depression. Lamar evinces a tempered delivery throughout much of good kid, m.A.A.d city, working as a storyteller rather than a braggart rapper, further pushing his integrity, authenticity and validity as an artist. One of the best examples of this is on the twelve-minute epic, and potential magnum opus, ‘Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst’. The track is divided into three sections, with Lamar rapping from three different perspectives: part one from Dave, a late friend; part two from the sister of prostitute Keisha (this links back to Lamar’s debut studio record Section.80); part three from his own perspective.

When speaking from his perspective, Lamar discusses the desire to opt-out of this hazardous life – “Fuck! I’m tired of this shit! I’m tired of fuckin’ runnin’, I’m tired of this shit! That’s my brother, homie!”. It presents a poignant juxtaposition to many of his contemporaries’ attitudes, who have glamorised and romanticised the ‘gangster’ lifestyle. But Lamar states his frustration and tiredness in relation to this predestined way of life. Another clear example of Lamar’s desire to recount stories and experiences is that of the (half) titular track, ‘m.A.A.d city’. Lamar describes how being born in Compton automatically places you into gang culture – regardless of your personal beliefs or morals. Compton territories are mainly divided by who owns them – subsets of Pirus or Crips (the introduction to the track addresses this head-on – “If Pirus and Crips all got along, they’d probably gun me down by the end of this song.” In 2021, Compton had a violent crime rate of 1,142.41 incidents per 100,000 residents, with the national average for violent crime being 366.7 per 100,000 residents. Throughout ‘m.A.A.d city’, Lamar describes witnessing a vicious murder when he was only nine years old. His social awareness, even at that age, told him never to reveal who did it:

“Seen a light-skinned n***a with his brains blown out At the same burger stand where *beep* hang out. Now this is not a tape recorder sayin’ that he did it. But ever since that day, I was lookin’ at him different.”

‘m.A.A.d city’ marks the climax of the album’s story, swapping adolescence for sheer violence and brutality. Production-wise, this titular track is a clear nod to the West Coast rap sound that has greatly inspired Lamar over the years, with its booming drums and G-funk elements. It also features a fantastic, featured verse from MC Eiht of gangsta rap group Compton’s Most Wanted.

Lamar’s verse on ‘m.A.A.d city’ also references another theme of the record: family. The casualty in question was Lamar’s Uncle Tony. While this occurred during the early nineties, it still highlights the sheer brutality of growing up in Compton. Lamar has said himself that murder was something you had to get used to, especially as a child. This article by Rolling Stone details some of these family ties in more detail and is definitely worth looking into to gain a deeper understanding of the record. But despite the chaos of Compton, Lamar still has sniper-level precision in terms of recalling events, such as the line “Me and my n****s four deep in a white Toyota/A quarter tank of gas, one pistol, one orange soda’ from the track ‘The Art of Peer Pressure”.

Though the loose narrative of good kid, m.A.A.d city is a general overview of Lamar’s adolescence in Compton, it truly cuts deep into the subject of family, something incredibly important in this culture. The record also delivers some of Lamar’s finest tracks and verses – and some killer features, most notably Jay Rock’s verse on ‘Money Trees’. Jay Rock growls throughout his verse, painting vivid imagery of Compton for the listener. Though a lot of the tracks spotlight Lamar’s lyricism, you cannot deny the sheer ferocity of some of the production – especially ‘Backseat Freestyle’ (produced by Hit Boy) and ‘m.A.A.d city’ (produced by Sounwave). Going back to ‘Money Trees’, it gives us one of the best and most recognisable samples in Lamar’s discography to date (if not in all of 2010s hip-hop). The iconic introduction, and passage that flows throughout the song, is simply the main motif of Baltimore-duo Beach House’s ‘Silver Soul’ reversed. There is no clever, J-Dilla-esque or Madlib-style chopping; DJ Dahi simply reversed the audio file and subsequently gave the world an instantly identifiable hit.

The album is one that delves deeply and spiritually into the world that the majority of us are so unfamiliar with. It is an unfiltered look at Compton but gives us stories rather than sheer shock value or concertation, something all too common with albums delving into difficult concepts and tales. good kid, m.A.A.d city is one of the most definitive albums of the 2010s – and arguably one of the most definitive hip-hop albums ever. Ten years since its release, very little of the record has aged at all, and some of the cuts here still stand as some of the best in Lamar’s discography. It set the foundations for Lamar’s later albums—To Pimp a Butterfly and DAMN.—with the former evolving Lamar’s passion for storytelling and narration. Without good kid, m.A.A.d city, it is unlikely the sheer perfection and cultural impact of To Pimp a Butterfly would have materialised, therefore establishing the former as one of the greatest hip-hop records ever made.

Our Music Made Us campaign is told through the students, graduates, journalists, experts and passionate people who have been shaped by this creative outlet. Discover their stories here.