Sarah Drew, screenwriting lecturer at Screen and Film School Birmingham, recently held a wonderfully in-depth and informative virtual workshop on screenwriting as part of our ever-popular Easter Series.

Sarah offered such a rich abundance of insight and knowledge to participants in the workshop that it’s been impossible to fit it all into one article. So, this is part one. For part two, click here.

In this first part, Sarah delves into narrative structures in screenwriting, invoking the structures set out by industry heavyweights including William Goldman, Syd Field and Blake Snyder, explaining how these structures can be used to enhance your storytelling and create worlds, characters and plots that engage and delight audiences, and – crucially – improve your chances of success when pitching your script to executives.

If you missed the session, you can check out the recording right here:

Sections:

- Embracing your crazy

- The three-act structure

- Syd Field’s three-act structure

- The three-act structure in short film

- Blake Snyder: Save the Cat

Embracing your crazy

“It’s an accepted fact that all writers are crazy; even the normal ones are weird.” – William Goldman

William Goldman, one of the most famous screenwriters of all time, who wrote Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, speaks to the fact that, as writers, we’re filled with ideas. You’ve got to have a certain healthy amount of crazy going on in your head to be able to imagine being multiple different characters and weave them into impactful stories.

Goldman’s work is highly recommended for anyone getting into screenwriting. Reading his novels, his scripts, and his book Adventures in the Screen Trade: A Personal View of Hollywood and Screenwriting, are all outstanding resources that will give you a solid foundation in the working practice of a master of the genre.

You’ll also find valuable insights by looking at the works of luminaries like John Truby, Blake Snyder and Syd Fields. If you prefer more conventional narrative structures, Field and Snyder offer ideal frameworks for structuring your screenplay. If you’re drawn to more unconventional storytelling approaches, Linda Aronson’s The 21st Century Screenplay offers a treasure trove of techniques, exploring concepts like parallel narratives and multi-protagonist storytelling. A good example of these techniques is Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994).

The Three-Act Structure

Understanding the three-act structure is fundamental for any storyteller. While it serves as a bedrock for storytelling, variations like the six-act structure or even seven-act structure do also exist. In theatre, a two-act play might further subdivide in its second act. But whether you decide to stick to or diverge from the three-act structure, grasping its fundamentals is essential.

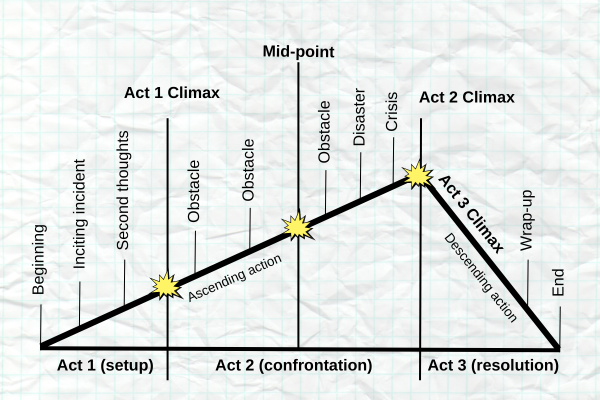

Syd Field’s Three-Act Structure

Act 1

Act 1 begins by showing your central character(s) in their normal world. Then, within quite a short space of time (normally between 3 and 15 minutes in), the inciting incident occurs. From here, the protagonist is propelled into a new ‘realm’, where challenges and problems will need to be overcome and conflicts resolved.

As second thoughts set in, the protagonist grapples with a task laid before them by the inciting incident. At this point they’ll be unsure about their ability to undertake the journey or fix this problem, vacillating between avoidance and contemplation.

We then reach the climax of Act 1, which would typically be the moment where the protagonist realises they don’t have a choice but to answer the call to action.

Act 2

As we enter Act 2, tensions begin to rise as the protagonist commits to overcoming the challenge, only to encounter obstacles that defy easy solutions. Each hurdle intensifies the struggle, until we reach the mid-point, characterised by a significant revelation or shift.

This mid-point marks a substantial change in the narrative’s trajectory. An example would be the ‘chest-bursting’ moment in the film Alien (1979). Up until this point, the film has seemed to be a space drama, but at this moment it becomes a full-on horror film.

Another example of the mid-point would be the moment in Jurassic Park (1993) where we discover the T Rex has escaped. The notion of this park being a place of fun and exploration has gone; now, it’s all-out chaos – the system has failed and everyone is now fighting for their lives.

A slightly different example of the mid-point would be the revelation of Amy’s survival in Gone Girl (2014). In Psycho (1960), it’s the shower scene. Even in sweeter narratives, we see the mid-point in action. The moment in Toy Story (1995) where Woody and Buzz are thrown from the car and are suddenly alone; they’ve been removed from their safe environment and have to fend for themselves.

You can consider film narrative in terms of stakes. The stakes have to keep getting higher. At the midpoint, we become fully aware that everything has hit the fan.

Another obstacle comes next. Things have to keep getting worse for your protagonist in Act 2. In a comedy, we strip away the façade to reveal the character’s raw essence, often through further misfortune, in order to transform them in Act 3. In this genre, the post-mid-point obstacle would be further example of something dreadful happening to the character.

Then, we hit the disaster; the moment where hope seems lost. The crisis, primarily internal, instils doubt not just within the audience, but within the protagonist themselves. But through a little soul searching or a twist of fate, they have an epiphany – a realisation that they must fight on and forge a new path forward, to Mordor for example, or wherever it is they need to go.

The climax of Act 2 typically unfolds as a battle of some kind. It’s time for the lightsabres to come out. This showdown or final challenge leads to the protagonist’s triumph, whether it’s winning the epic battle, reaching the summit, or securing the affection of their love interest.

Act 3

As we enter Act 3, the action begins to descend. This act is a shorter segment than the first two acts, as we guide the protagonist back to a semblance of normality, albeit a ‘new normal’ altered by their journey. Loose ends are tied up as we approach the resolution, the end of the narrative journey.

The three-act structure in short film

When we consider the three-act structure in the context of short film, the setup in Act 1 can be incredibly brief, sometimes just a few seconds. The bulk of the narrative unfolds in Act 2, characterised by confrontation – a pivotal moment for the main characters. Act 3, the resolution, may also be brief, especially in genres like horror, where a jump scare could serve as the culmination, again lasting only seconds.

The versatility of the three-act structure is evident across all areas of filmmaking. While short films offer more room for experimentation, using a three-act structure can provide a solid template for if you’re feeling a bit lost with your writing. It serves as a reliable framework that ensures coherence, even in the condensed format of the short film.

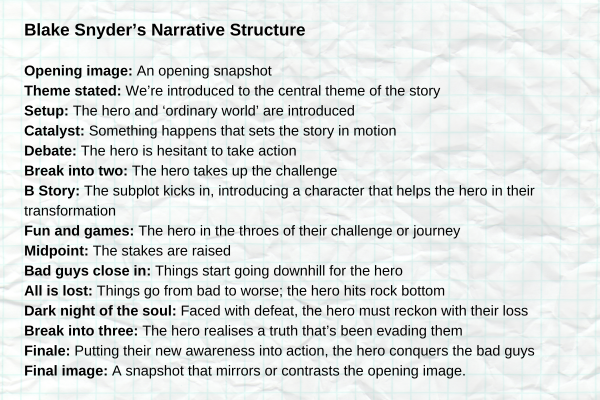

Blake Snyder: Save the Cat

Blake Snyder’s book, Save the Cat, is another fundamental guide for screenwriters, emphasising the importance of crafting likeable protagonists through defining moments. The concept refers to showing the character has a sense of altruism early on, which will ensure that the character wins favour with the audience. A simple act, like saving a cat from a tree, humanises the protagonist and establishes a connection with the audience.

Snyder’s approach offers a really effective breakdown of the formula for films. While studying screenwriting, you should aim to read multiple books on screenwriting structures, but Save the Cat is probably the most accessible and arguably the most important to read. One of the reasons it’s so important for screenwriters is that it introduces terms that are commonly used in the industry. So, for example, if you’re pitching your film to an executive, a director, or a producer, they might ask you about what happens in the ‘dark night of the soul’ or about your ‘all is lost’ moment. This is the language that’s spoken, and you’ll need to know it.

Central to Snyder’s approach is the notion of an opening image, an opening snapshot that sets the tone and introduce the protagonist’s world. At this point, you should also be aiming to show the audience who your character is.

The theme is stated typically around page 5, and articulates the story’s central message or moral, often through interactions with secondary characters. It’s unlikely that the theme would be stated by the central character themselves, but by another character either directly to the protagonist or indirectly to the audience.

The setup spans pages one through ten, establishing the protagonist’s ordinary world and underlying conflicts. This segment is crucial for revealing the character’s weaknesses, traumas, and motivations, often through an exposition of their back story.

The catalyst is the equivalent of Field’s inciting incident, something that sets the story in motion, prompting the protagonist to confront their internal and external challenges in the debate segment. Act 2 unfolds as the protagonist embraces the challenge, as they realise they can’t escape following the journey that they need to pursue.

Snyder then talks about the B-story, or subplot, where we’re introduced to a character or characters who’ll help the protagonist in their transformational journey. These supporting figures, whether mentors or allies, play a key role in the protagonist’s growth. This B-story is introduced at around the 20-minute mark, according to Snyder, who’s quite prescriptive about what you should be doing on each page of your screenplay.

The fun and games segment, lasting around 20 to 25 minutes, is where the hero is in the throes of their challenge or their journey. Fun and games isn’t necessarily an accurate description, though. For example, let’s say you’re writing a prison drama; this segment would be more about the character learning what the rules of that world are, pushing against their boundaries so they can understand their situation.

Snyder talks about the fun and games section as containing the ‘trailer moments’; the moments that will entice audiences to watch your film, providing a glimpse into the challenges and stakes at play, the characters, and a bit of back story.

Next, we have our mid-point, where tensions rise and obstacles mount. The midpoint ‘twist’ heightens the stakes, compelling the protagonist to redouble their efforts. However, adversity looms as the bad guys close in, and the hero’s journey takes a darker turn. Things go from bad to worse and our hero hits rock bottom, often a moment where somebody dies, where we think someone has died, or somebody leaves; someone important to the hero and their journey is suddenly not there anymore. This is Snyder’s all is lost segment.

As we move into the dark night of the soul, our hero is faced with defeat and must reckon with their loss and how they got there. At this part, you tackle the internal trauma of your central character. A weakness that they’ve not yet overcome – a demon in their past, something they’ve not dealt with, or a lost love, for example.

The dark night of the soul is about internal exploration, coming face to face with their demons. This is the deep stuff that even the lightest of movies needs.

Next, we break into Act 3. This is the equivalent of the climax point in Fields’ three-act structure: the lightsabre scene. At this point, the hero realises a truth that’s been evading them, and we begin moving towards the finale as they put their new awareness into action. They conquer the ‘bad guys’, in some form or another.

As the action descends, we move into the final image, the snapshot that mirrors or contrasts to the opening image.

An outstanding example of that opening image/final image is in The Wizard of Oz (1939). At the opening, Dorothy is in Kansas with her aunt and uncle, she’s lonely and wishes to escape to somewhere else, somewhere ‘over the rainbow’. She goes off on the journey to Oz and it’s a big adventure, before she returns to Kansas, which is the same world only changed by her altered perception, as she appreciates her home with fresh eyes. The concept of mirroring the opening and final images, while viewing the world through a transformed lens, underscores the power of a well-crafted journey.

Read more: So you want to be a screenwriter? Part 2