Adam Collins, one of our talented cinematography lecturers at Screen and Film School, recently hosted a captivating virtual workshop on cinematography as part of our ever-popular Easter Series.

The session began with an insightful breakdown of the camera and lighting departments within a film set, alongside the multifaceted responsibilities of a cinematographer, setting the stage for an exploration of iconic moments in cinema history.

Spanning from the early days of filmmaking to the present day, Adam meticulously dissected cinematic techniques and the technological advancements that have shaped them. From the pioneering days of silent films to modern innovations such as LED walls and drone photography, attendees left the session with a newfound understanding of the art and science behind cinematic storytelling.

If you missed the session, don’t worry! We’ve put together this comprehensive rundown of the highlights from the workshop. Get ready to uncover the secrets behind some of the most memorable moments in cinematic history and gain valuable insights into the art and craft of cinematography.

Sections:

- The role of the cinematographer

- The camera crew

- The lighting department

- Cinematic lighting

- Early cinematography: The Great Train Robbery

- Early innovators in cinematography: Billy Bitzer and Intolerance

- Shadow in film history: German Expressionism and Film Noir

- Old Hollywood vs New Hollywood

- Shifting aesthetics in New Hollywood

- The evolution of the tracking shot

- The Steadicam

- Colour in cinematography

- Seamus McGarvey on the use of colour in cinematography

- Framing and shot types

- The power of unconventional shots

- Framing for fear

- Modern cinematography: Innovations in action films

The role of the cinematographer

A cinematographer’s role encompasses a broad range of responsibilities throughout the filmmaking process. From pre-production to post-production, cinematographers play a key role in shaping the visual style and narrative of a film.

On set, the cinematographer will oversee the camera and lighting crews and ensure that each shot aligns with the director’s vision. They may block scenes in advance, plan camera moments, and adjust lighting to achieve the desired aesthetic.

The camera crew

A typical camera crew consists of several key roles:

- Camera Operator: Responsible for operating the camera and capturing the desired shots.

- First Assistant Camera (1st AC): Also known as the focus puller, the 1st AC manages camera focus, marks, and lenses.

- Second Assistant Camera (2nd AC): Historically known as the ‘clapper loader’, the 2nd AC assists with loading memory cards and maintaining camera equipment.

In addition to the core camera crew, there are also specialist roles in the department, such as:

- Key Grip: Mounts the camera on various rigs and oversees grip assistants.

- Grips: Assist the Key Grip and lay down track for camera movement.

- Crane Operator: Operates specialised equipment for crane shots.

- Steadicam Operator: Controls the Steadicam device for smooth, stabilised shots.

The lighting department

At the helm of the lighting department sits the Gaffer, who oversees the entire lighting setup on set. Assisting the Gaffer is the Best Boy Electric, who acts as the second in command and helps to coordinate the electric team.

Underneath the Gaffer and Best Boy are the Sparks, or electricians. These team members are responsible for setting up and operating the lighting equipment on set. They work closely with the Gaffer to achieve the desired lighting effects for each scene.

Riggers assemble scaffold towers and rig lights, and Practical Sparks focus on setting up practical lights, such as lamps or fixtures that appear on screen as part of the set dressing.

While the cinematographer typically leads the camera and lighting departments, their influence extends far beyond these areas. They will determine the overall look, colour and lighting of a scene, along with managing shots, setting up scenes, and ensuring visual consistency. The responsibility over the film’s visual style involves close collaboration with all areas of the art department – the production designer, art director, set decorators, prop masters, costume designers, and so on.

Cinematic Lighting

Lighting is the most important tool a cinematographer has in shaping mood and atmosphere. The position, colour, and quality of lighting shapes the visual narrative and can dramatically alter emotional tone. It has a powerful impact on the audience’s experience and how they interpret a scene. Essentially, cinematic lighting is a communication tool with intricate nuance, so a cinematographer must be meticulous in their understanding of the unspoken messages being portrayed through how a scene is lit.

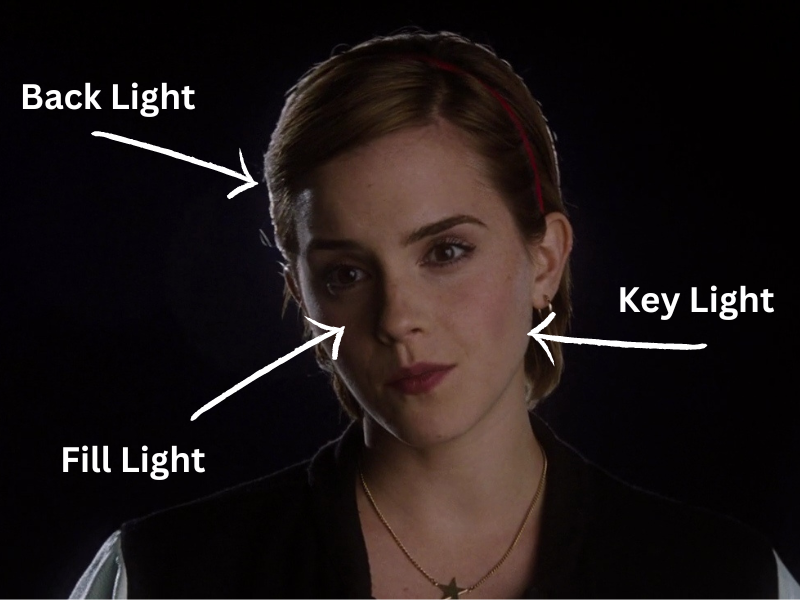

One key technique employed by cinematographers is the three-point lighting setup. While not always adhered to rigidly, it is an essential principle for crafting compelling visual narratives in filmmaking. The three-point lighting technique comprises:

- Key Light: The primary light source that illuminates the subject and sets the tone for the scene. Typically, the Key Light illuminates one side of the subject’s face, providing definition and depth.

- Fill Light: Positioned opposite the Key Light, the Fill Light softens shadows created by the Key Light, ensuring balanced illumination and preventing hard contrasts.

- Backlight: The Backlight is placed behind the subject, adding separation between the subject and background, enhancing visual depth and dimension.

© 2011 – Summit Entertainment, LLC.

In this image, from The Perks of Being a Wallflower (2012), we see a great example of negative fill. Negative fill refers to the intentional creation of shadow on one side of the subject, adding definition and dimensionality to the image. By introducing shadow on the reverse side of the subject, features such as the nose and eyes are accentuated. By contrast, if you were to light the subject from the front, it would flatten the facial features, minimising any definition.

The most impactful use of lighting we see in this shot, however, is backlighting. The light source is placed behind the subject, achieving a halo effect. While visually engaging, the use of backlighting here is also a subtextual choice; the ‘halo’ implies an angelic aura. In the context of the scene, where we know that Emma Watson’s character is the love interest, this lighting is used to communicate how Watson’s character is seen by the male character who’s interested in her. It’s worth noting that, though the halo effect can seem artificial, contextually it works here as the scene is at an American football game, lit by floodlights.

Early Cinematography: The Great Train Robbery

To understand the evolution of cinematography, it’s important to go back to the early days of filmmaking. The Great Train Robbery, from 1903, is an early example of narrative cinema, marking the transition from experimental filmmaking to structured storytelling. However, as celebrated as the film is for its narrative innovation, it’s clear that lighting techniques at the time were still rudimentary by contemporary standards.

The scene looks very much like a theatre stage, illuminated by natural sunlight. While modern filmmaking practices involve sophisticated lighting arrangements, sets like this one were often constructed outdoors or without roofs and relied on natural daylight. While we can see a lot of camera techniques being utilised, the art of cinematic lighting had yet to be established.

Early innovators in cinematography: Billy Bitzer and ‘Intolerance’

As the art of cinema evolved in the early 20th century, pioneering filmmakers like Billy Bitzer, working alongside D W Griffith, were instrumental in developing a new ‘visual grammar’ for cinema through the innovative use of lighting and composition.

Released just a decade after The Great Train Robbery, Intolerance (1916) represents a significant leap forward in visual storytelling. Lighting is used not only to illuminate the scene, but also to convey mood and atmosphere.

Bitzer’s use of atmospheric effects, such as shooting through haze and smoke, remains influential in modern cinematography. You can see the same technique used to great effect in this iconic shot from The Exorcist (1973):

The depth and texture that the technique adds to the scene was so effective at drawing viewers into the unsettling world of The Exorcist and its eerie, ominous atmosphere, that the shot has become an instantly-recognisable cultural image that has transcended its use even in promotional materials and posters for the movie.

Shadow in film history: German Expressionism and Film Noir

Cinematic lighting is about more than just illuminating a scene; it’s about using light and shadow to shape the mood and atmosphere, and add narrative impact. By strategically controlling the interplay of light and shadow, filmmakers can create depth, tension, and emotional resonance.

In the 1920s, German Expressionism emerged as a movement characterised by bold visuals and dramatic lighting. Stark contrasts between light and shadow are used to convey psychological depth and intensity. This iconic clip from Nosferatu (1922) is a great example of how effectively shadow is used in the genre:

Taking its lead from German Expressionist cinema, the film noir movement of the 1940s and 1950s utilised low-key lighting and deep shadows to create a sense of mystery and moral ambiguity.

See how this clip from The Maltese Falcon (1941) exemplifies how minimal light and strategic shadow placement can heighten tension and drama:

In both German Expressionism and film noir, shadow is not merely the absence of light but also a powerful tool for narrative expression. By manipulating shadow and light, filmmakers convey emotion, tension, and thematic depth in a way that has profoundly shaped the visual language of cinema.

Old Hollywood vs New Hollywood

The transition from old Hollywood to new Hollywood marked a significant shift in the approach to cinematic lighting mid-way through the 20th century. Changing artistic sensibilities and influences from European filmmakers in the late 1960s challenged traditional Hollywood conventions. The European emphasis on realism and innovation in lighting techniques reshaped American cinema, ushering in an era of experimentation and artistic freedom.

While old Hollywood favoured spectacle and glamour, new Hollywood embraced a more emotionally resonant approach. We can see this contrast very clearly when we compare The Searchers (1956) to Taxi Driver (1976). The Searchers is a quintessential example of old Hollywood cinema. High key lighting dominates; the scene is bathed in light, highlighting the characters’ faces and defining features. Fast forward to Taxi Driver, and we see the European influence full-force: the lighting is more subdued and naturalistic. Rather than flooding the scene with light, the cinematographers focus on shaping light to create realistic yet dramatic shots. This departure from high key lighting reflects the shift towards grittier, more immersive storytelling styles.

Shifting aesthetics in new Hollywood

Gordon Willis, a renowned cinematographer of the era, raised eyebrows on set when he insisted on employing a technique known as top lighting on The Godfather (1972).

The technique involves placing lamps above the actors’ heads to cast shadows under their eyes, creating a sinister appearance – and also making them look much older. Marlon Brando was in his 40s when The Godfather was filmed, and his character is an ageing mafioso, so the use of this technique, right from the opening scene, communicates his advancing years whilst also accentuating the film’s themes of corruption and moral ambiguity.

Willis’s top lighting technique is used to similar effect by cinematographer, Lawrence Sher, in Joker (2019). The casting of shadows with overhead lighting is used to accentuate the protagonist’s emotional turmoil, his rapidly changing facial expressions emphasised by deep shadow and contrast.

The evolution of the tracking shot

The evolution of cinematic camera techniques has played a crucial role in shaping the visual language of filmmaking.

In the early days of filmmaking, stationary cameras were all we had, which goes a long way to explaining the stage-theatre aesthetic we saw in The Great Train Robbery. When the moving camera was introduced, it added a dynamism to the way in which cinema could be filmed, and allowing filmmakers to create more immersive narratives.

The tracking shot, achieved using a dolly and track, quickly became a standard technique in cinematography. By mounting the camera onto a vehicle weighed down by tracks, filmmakers could now capture smooth, gliding shots that elegantly followed the action. Even now, with so many technological advancements at our disposal, the tracking shot remains a tried and true method for achieving fluid camera movement.

A fantastic early use of the tracking shot can be seen in Wings (1927). In this groundbreaking sequence, the camera moves seamlessly through tables crowded with people. A succession of different stories are told at each table, all communicated in this single shot, as though the viewer is moving through space. What’s clear from this example is that, once you start moving the camera, you open up opportunities to involve the audience in new ways, and really immerse them in the action.

The Steadicam

In the mid-1970s, Garrett Brown introduced a game-changing new invention to the world of cinematography: the Steadicam. The device transformed the way filmmakers captured motion, offering unparalleled stability and versatility in camera movement.

Unlike traditional shoulder-mounted cameras, the Steadicam allowed users to separate themselves from the camera, thanks to its articulated arm system. The impact of footsteps and other movements on shot stability was removed, resulting in remarkably smooth footage regardless of terrain.

This versatility allowed filmmakers to achieve complex tracking shots previously impossible with conventional track and dolly setups. The Steadicam was instrumental in the way that Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) was shot. Many of Kubrick’s sets for the film were tremendously convoluted, particularly the hedge maze, and simply couldn’t have been photographed the way Kubrick intended without the use of the Steadicam.

Jumping ahead to 1990, we see a wonderful example of the use of the Steadicam in action in Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas. The fluidity and energy conveyed in this sequence owes a lot to the Steadicam, which allowed all of this action to be filmed in a single take.

Colour in cinematography

Colour plays a pivotal role in shaping the visual aesthetic and enhancing the storytelling of a film. Colour serves as a potent tool for cinematic storytelling, influencing mood, atmosphere, and character dynamics. Through strategic use of colour palettes, filmmakers use colour as a language through which to immerse viewers in the cinematic world they’re creating.

In Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), the dominant cool tones evoke a sense of coldness and detachment that reflects the unfeeling nature of the robot characters. The metallic blue hues create a stark, clinical atmosphere, reinforcing the theme of merciless machines devoid of empathy.

The colour palette extends beyond the lighting in Terminator 2. It is apparent in the costume design and set decoration; the characters’ blue clothing and the sterile laboratory environment further immerse viewers in the film’s dystopian world. Every aspect of the visual composition contributes to conveying this underlying theme.

Seamus McGarvey on the use of colour in cinematography

Framing and shot types

© 2010 The Weinstein Company

In The King’s Speech (2010), unconventional framing and shot types are used to evoke emotion and convey the character’s internal struggles. Take, for instance, the shot above. At first glance, the framing of this shot may appear perplexing, but when viewed through the lens of storytelling, its significance becomes clear.

The choice to frame the character against this expanse of nothingness serves to emphasise his isolation and loneliness. Prince George VI, grappling with a speech impediment, is in a state of vulnerability. By isolating him in the frame, the audience is invited to empathise with his struggle and his sense of isolation.

The wall, though seemingly mundane, carries symbolic weight. Its worn textures and muted colours reflect the character’s turmoil and the harsh realities of his royal position. The choice to highlight the imperfections and decay on the wall’s surface further underscores the challenges the prince faces.

The power of unconventional shots

By breaking conventional filmmaking rules, such as adhering to traditional shot compositions, the film challenges viewers to engage with the narrative on a deeper level. Visual information is not spoon-fed; interpretation and introspection are encouraged.

While unconventional framing, like in this example from The King’s Speech may initially appear jarring, it possesses a unique power to evoke emotion and provoke thought. Shots such as these serve as visual metaphors for the character’s journey, and the audience is invited along to share in his struggles and triumphs.

Framing for fear

Framing and shot types are not just technical choices, but powerful storytelling tools that shape the audience’s perception. Through deliberate framing and composition, filmmakers can convey complex themes and evoke profound emotional responses.

In this scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), we see the character Arbogast ascending the stairs (TS: 1.14) framed in a mid-shot that conveys his vulnerability and isolation. As he reaches the top landing, the camera abruptly switches to a high-angle shot.

From this high-angle shot, the viewer is removed from the scene, observing it as detached from reality. From whose perspective is the audience viewing this scene? Could it be that of a character who is similarly detached from reality themselves?

As the attack unfolds, Hitchcock employs rapid cuts and close-ups to disorient the viewer and, thus, amplify the horror of the moment. The use of extreme close-ups on Arbogast’s face captures his terror and desperation, while the frenetic editing heightens the sense of chaos and confusion.

Modern cinematography: Innovations in action films

In the realm of modern cinema, films like Top Gun: Maverick (2022) offer cinematographers an opportunity to showcase the pinnacle of new technology. While action movies may sometimes be criticised for leaning heavily on cliché, the cinematography often stands out for its brilliance at capturing the thrill and intensity of the scenes.

In Top Gun: Maverick, wide shots of planes soaring through the sky are juxtaposed with intimate perspectives from inside the cockpit. This approach immerses viewers in the heart-pounding action, allowing them to feel like they’re riding right alongside Tom Cruise in the cockpit.

The behind-the-scenes setup of Top Gun: Maverick shows us quite how far camera technology has come. Using state-of-the-art Venice digital cameras, filmmakers can capture multiple angles simultaneously with compact sensor units placed strategically within the aircraft. Without the need for bulky equipment, cameras can be seamlessly integrated into the action.

Aerial shots are now shot using drones, whereas in the past a helicopter would have been necessary in order to catch some of the shots seen here. Drones allow these shots to be achieved with great flexibility and efficiency by a single drone operator.

Finally, LED technology has now revolutionised set lighting, offering filmmakers unprecedented control and versatility. LED walls serve as dynamic backdrops, allowing for immersive environments that spill light onto the set in a way that is both lifelike and interactive for actors and crews to work with.